[Last year’s Good Friday homily, preached on March 29, 2013.]

Good Friday. Good Friday. Good Friday.

Good Friday. Good Friday. Good Friday.

How could anything like this be good?

He was an innocent man. Even the criminal said of him, “This man has done nothing wrong.”

An innocent man. No, more than that: the best of men.

The most human of us all. The one who was and did as we were created to be and do. The one who lived as we were supposed to live. The one who loved as we were supposed to love. The one who gave as we were supposed to give and served as we were supposed to serve. The one who showed God to the world—in all his subversive goodness, in all his inexplicable humility, in all his infinite grace and prodigal mercy.

The one who said, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near,” and he should know, because he brought it. The one who said, “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you,” and did just that. The one who said, “Your sins are forgiven; now go and sin no more,” and then made that possible.

The one who healed the broken and touched the untouchable, who welcomed the outcasts, lifted up the oppressed, associated with unsavory characters, who was called “a friend of sinners” and wore it as a badge of honor because he came to seek and to save the lost.

This man is rejected.

But more than that, not even just a simple, “No, thanks.” No, his disciples run away in his time of need; his closest friend denies him—not once, but three times; and so this man, who entered Jerusalem only days earlier to adoring crowds, is now hanging on a cross, triumphant cheering turned to derisive jeering.

This man cries out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Jesus took on the sin of the world. “The sin of the world.” Such a small phrase for such a large burden.

Every time we sin, we choose a reality opposed to that for which we were made. We choose by our actions to be separated from God, the creator and designer and source of life. When we lie or when we walk past someone in need or when we hurt those who care about us or when we choose to gratify ourselves at the expense of others, sexually, emotionally, relationally, financially—when we choose anything other than life with God, which is what we were made for, we choose death.

It’s as if we are keys, made to fit the door of life with God, and we’re grating and grinding and scraping and pieces are being broken off because we’re trying to open all these other doors, and it’s not getting us anywhere. Or at least, not anywhere good.

Now think about those decisions, drawn out over the course of your life, however many years you’ve been around. And now think about those lives, drawn out across the planet—six billion people. And now think about the course of human history, drawn out across time—thousands and thousands and thousands of years, billions and billions of lives, a multitude of decisions choosing death. Is it any wonder our world is hurting?

And now bring it back to you.

And to Jesus, the one who lived as we should have lived and died the death we should have died. To paraphrase John Stott:

The essence of sin is that we substitute ourselves for God; we put ourselves where only God deserves to be … that’s the essence of sin. But the essence of salvation is that God substitutes himself for us; God puts himself where we deserve to be … that’s the essence of salvation.[1]

You might remember the story in Genesis, when Adam and Eve reject God’s command and sin against him, and one of the results is that the ground is cursed—Genesis 3:18 says, “It will produce thorns and thistles.” On Good Friday, we see the king of all creation, crowned with thorns, quite literally wearing the effects of human sin, little bits of cursed ground.

Jesus is the only one who could have saved us. Imagine the climber who’s made it to the top where no one has managed it before, where no one has even come close, and he throws down a rope and says, “I’ve got you; I’ll pull you up.” And though you’re tired from straining and struggling, and you’ve got cuts and bruises, and actually, despite your best efforts, you’re still a lot closer to the ground than you are to the top, he says, “I’ve got you; I’ll pull you up.”

Only this climber is actually hanging on a cross, and his method of pulling you up is by laying down his life for you. One writer put it this way:

As far back as recorded time and doubtless before, kings, princes, tribal chiefs, presidents, and dictators have sent their subjects into battle to die for them. Only once in human history has a king not sent his subjects to die for him, but instead, died for his subjects.[2]

Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ, came to redeem, to rescue, and to restore all of creation—including us. This is God’s great plan: “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.”

Because even till the end, even in suffering, even in death, he fulfills his mission: to show God’s reign, to be a sign of God’s kingdom—this is what it looks like when God is here.

- He says to the criminal who seeks him, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise.” Because of what I am doing right now, there is grace—amazing grace.

- He says to his mother and he says to his dear friend John, “Look after one another.” I came that you might have real and eternal life, more and better life than you ever dreamed of—but it isn’t just some pie-in-the-sky, out-there-in-the-great-unknown kind of life; it is real, and it is tangible, and it is practical. This command I give to you: love one another.

“The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.” It cannot overcome it.

This is Good Friday.

—

[1] John Stott: “The essence of sin is we human beings substituting ourselves for God, while the essence of salvation is God substituting himself for us. We … put ourselves where only God deserves to be; God … puts himself where we deserve to be.” Quoted in Timothy Keller, The Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism (New York: Riverhead Books, 2008), 202.

[2] Charles Colson and Harold Fickett, The Faith: What Christians Believe, Why They Believe It, and Why It Matters (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2008), 90.

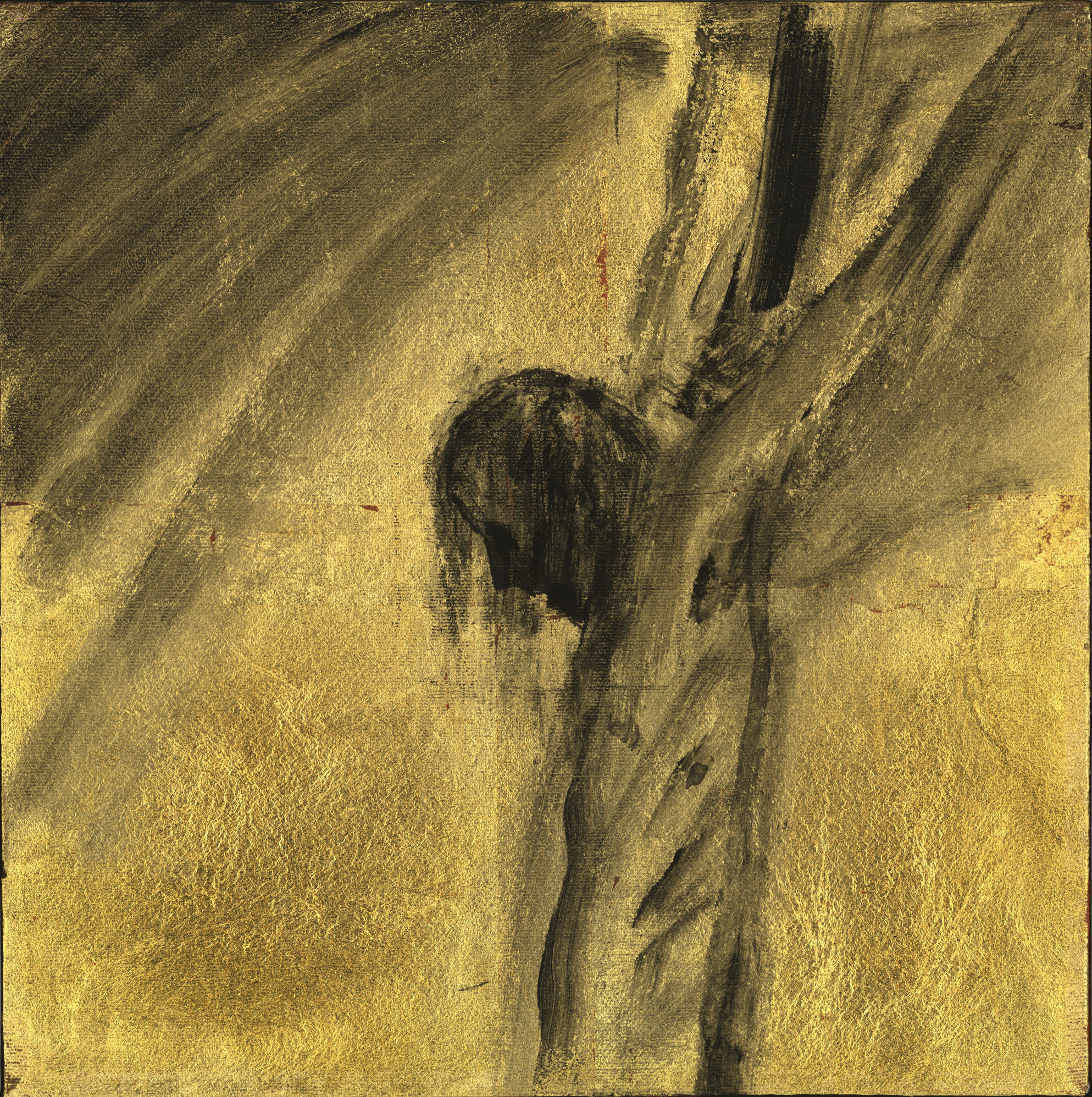

[Painting by Audrey Anastasi. Check out the rest of her amazing Stations of the Cross.]