[Adapted from yesterday’s message at The District Church: “Who is My Neighbor (and Why Should I Care)?”]

What do you think of when you hear the word ‘neighbor’?

Mr. Rogers?

Mr. Rogers?- The folks on Sesame Street?

- Wilson from Home Improvement? Or Mr. Wilson from Dennis the Menace?

- The Australian soap opera I grew up watching in Hong Kong: “Neighbors, everybody needs good neighbors …”?

One of the things about the Christian faith is that it’s very practical and very tangible—or at least, it’s supposed to be. In Luke 10, Jesus is asked by a lawyer, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” And Jesus replies, “Well, you’re an expert in the law—what does the law say?” And he says, “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, mind, soul and strength,” a sentence from the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4), a sentence that would have been recited three times a day by devout Jews. And then he tacks on—rightly, according to many rabbis of the day—Leviticus 19:18: “Love your neighbor as yourself.”

The people around him would have been like, “Man, this lawyer guy knows his stuff.” Because throughout Scripture, love of neighbor is lifted up, shown to be important to God.

- Prov. 3:28 Do not say to your neighbor, “Go, and come again, tomorrow I will give it”—when you have it with you.

- Prov. 14:21 Those who despise their neighbors are sinners, but happy are those who are kind to the poor.

But what does Jesus say? Does he say, “You have given the right answer; you will live”? No, he says:

“You have given the right answer; do this, and you will live.”

How much easier is it to give the right answer than to back that up with the way you live?

A lot.

We’ve just started an Art of Neighboring series at The District Church, and it’s based on the book by Dave Runyon and Jay Pathak. At the core of the book—and our series—is this simple question:

We’ve just started an Art of Neighboring series at The District Church, and it’s based on the book by Dave Runyon and Jay Pathak. At the core of the book—and our series—is this simple question:

What if we all did what Jesus said and loved our neighbors — our actual, next-door, flesh-and-blood neighbors?

Dave and Jay tell the story of how, five years ago, a group of pastors in the Denver area got together to think, dream, and pray about how their churches might serve their local community together—they had a similar heart and passion for their city as we do. They invited their local mayor, and asked what the community needed and how they could help. He said:

Dave and Jay tell the story of how, five years ago, a group of pastors in the Denver area got together to think, dream, and pray about how their churches might serve their local community together—they had a similar heart and passion for their city as we do. They invited their local mayor, and asked what the community needed and how they could help. He said:

The majority of the issues that our community is facing would be eliminated or drastically reduced if we could just figure out a way to become a community of great neighbors.

Now, as we’ll see, ‘neighbor’ can be anyone we encounter who’s in need, but I think it can be real easy for us to uncouple our understanding of ‘neighbor’ from ‘the people who live next door to us’ and then attach it to this large, nebulous group of ‘anyone who’s in need’, and actually end up loving neither. Dave and Jay put it this way:

When we try to love everyone, we often end up loving no one. If we are not careful, we can end up having metaphorical love for our metaphorical neighbors and the end result is that we actually do nothing.

That’s why we want to get practical with this ‘loving our neighbor’ thing.

We did an exercise yesterday where we took these block maps and we all tried to fill out the following information for each of our eight closest neighbors:

- Their name.

- Some basic fact about them.

- Something of depth about them (e.g. dreams, needs, desires, fears, spiritual journey, etc.)

Other churches that have done this neighboring series call this ‘the chart of shame,’ because typically:

- 10% of people can do all of #1,

- 3% can do #2, and

- less than 1% can do #3.

The point of the exercise is to expose the fact that many of us don’t know most of our neighbors’ names, let alone anything about them! But more than that, it’s meant to help us identify the gaps in our love of neighbor, and it’s meant to motivate us because we’re going to do this again when we close out this series in four weeks, and the goal is to have moved to a place where we can fill out a few more lines and, more important than that, where we know our neighbors a little better and can know how to love and serve them a little bit more.

J.R. Briggs, who spoke at our Leadership Community Retreat a couple months ago, found this stat: police departments around the country have reported that 80% of police house calls could have been avoided if neighbors simply watched out for and cared for others in their own neighborhood. And I just read a story about a woman in Michigan who passed away six years ago, but they only just found her mummified body because her bank account ran out of money to cover her bills and car payments. SIX YEARS AGO. Her neighbors said, “Well, she kept to herself, she traveled a lot …” My friend Duke, who posted it on Facebook, said: “Here’s a sad case for the importance of community: Stay connected; don’t turn into a mummy.” It’s also a case for the importance of good neighbors!

Let’s return to the story in Luke’s gospel. When we left them, Jesus had just challenged the lawyer not just to know his stuff but to do it as well. The lawyer’s embarrassed because he knows he’s not doing this as well as he ought to, so the text says (10:29):

But wanting to justify himself, he asked Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?”

In other words, “Okay, Jesus, you make a good point. Now tell me whom I need to love; tell me whom I’m obligated to love.” In those days, Jewish teachers would use ‘neighbor’ to refer to ‘fellow Israelite,’ and this lawyer’s trying to narrow that down even more. See, he’s trying to figure out who’s in this category of people he needs to love in order to qualify for eternal life—what’s the minimum I need to do?

We ask that question a lot, don’t we? It takes different forms, though:

- How far is too far?

- How hard do I have to try at work so that people won’t think badly because they know I’m a Christian?

- Do I tithe on my net or on my gross income? How much do I have to give so that I won’t feel guilty when you preach your sermons about stewardship?

We try to shoot for doing the bare minimum; we aim for we can get away with.

In this case, Jesus answers the lawyer with a story: “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho …” (10:30). And the lawyer’s thinking:

What kind of man? Was he rich or poor, Jew or Gentile, holy or unclean? Because that’s going to decide how I feel about him. Is he the protagonist? Am I supposed to feel sorry for him? Or is he a Gentile, in which case he probably deserved it?

Jesus doesn’t say. Jesus doesn’t say anything else about the man, and I think that’s intentional, because he knows how our hearts work. We make similar judgment calls:

Is this person rich or poor, old or young, attractive or ugly, gay or straight, married or single or divorced, a good parent or a bad parent, Christian or non-Christian, Republican or Democrat, conservative or liberal?

And then we put people in boxes so that we know how to treat them. If you’re rich or young or attractive, I’ll treat you this way; but if you’re old or poor or homeless or mentally ill or not hot, I’ll treat you this way. Jesus knows that the lawyer is thinking like this, and so he purposefully leaves this out. Whoever the man is, he’s waylaid by bandits, stripped, beaten, and left for dead.

No other information given; apparently, no other information necessary.

A priest comes along, and “when he saw him, he passed by on the other side” (v.31). Then a Levite (a temple worker) comes along, and “when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side” (v.32). You may have heard their motivations presented in a couple of ways:

- They didn’t care—the priest and the Levite had no heart, and so they didn’t just pass by; they passed by on the other side.

- They were afraid for themselves—who knows if the guy’s even still alive? What if the bandits are still around?

But the lawyer, and probably the people listening too, would have been nodding their heads in agreement, because they would have known that the Law of Moses says that if anyone makes contact with a corpse, he or she becomes ceremonially unclean. The book of Numbers says anyone who touches a corpse must then go through a period of cleansing, which would involve going back to Jerusalem and going through a purification ritual that would last seven days. How inconvenient would that be?

For priests and Levites, the requirements were even more stringent, because they worked in the temple—the house of God. Leviticus 21:11 says specifically, “A priest shall not go where there is a dead body; he shall not defile himself even for his father and mother.” The priests were to keep away from death and disease and ceremonial impurity—that was the command of God! Every single devout Jew who heard Jesus’ parable would have thought the priest and Levite were doing the right thing. They were obeying the law; that’s why they passed by on the other side of the road.

Jesus continues:

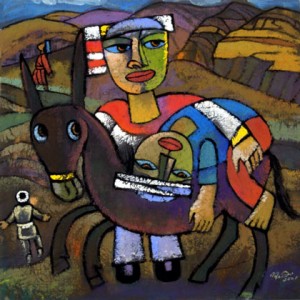

But a Samaritan …

Samaritans and Jews didn’t get along. There was long-festering, deep-seated, religiously-sanctioned hostility between the two groups of people. To the Jews, Samaritans were religious separatists, who had built their own temple on their own mountain, and they were heretics because their holy scriptures were different. Worse than that, one Passover early in Jesus’ lifetime, some Samaritans desecrated the Jerusalem temple by scattering bones in it—that’s like someone coming into your house, picking up your favorite possession, stomping it into the ground, and then burning it to ashes, only a thousand times worse.

Think about the person you get along with the least—the difficult colleague at work, the irritating relative who sends all those chain emails and has all those opinions you disagree with, the person who used to be your friend until she betrayed your trust, the person who used to be a mentor until he let you down, the guy who lives on the corner and is always raving and shouting and cursing at you, the neighbor who stays up too late and plays their music too loud or has friends over at all hours. Now imagine Jesus lifting that person up as the protagonist—the hero—of the story. That’s what Jesus is doing here.

The priest and the Levite see the injured man and pass by on the other side; that was their legal obligation. The Samaritan “came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with pity” (v.33). The Greek word is a fun one:

esplangchnisthe

It means, “he was moved in his gut, moved with compassion.” When was the last time you were moved in your gut—with compassion—for your neighbor—your next-door neighbor? One of my neighbors is really, really nice, but can also be a little socially awkward. And my problem is that I’ve put that neighbor into that ‘socially awkward’ box, which means that every time I think about interacting with that neighbor, my first thought is, Man, this is going to be awkward, rather than I don’t care what box others may put you in—you’re made in the image of God, I want to know your story. That’s how I think Jesus would want me to be.

The Samaritan doesn’t see Jew or Gentile, rich or poor; he sees a person in need, and he risks his own life—remember, who knows if the bandits are still around? He’s a Samaritan in Jewish territory; this wouldn’t have been the safest place for him. But he chooses to find out if the man is still alive rather than playing it safe. He doesn’t care about playing it safe; he doesn’t care about ceremonial cleanness; he doesn’t care about the letter of the law; he doesn’t care about who the man is.

“He went to him and bandaged his wounds, having poured oil and wine on them” (10:34). (The application of oil and wine was a form of medical treatment in those days.) Then he puts the injured man on his own donkey, checks him into an inn and puts his money where his mouth is, paying for his care, for food and for lodging. He meets the physical, material, financial, and emotional needs of the injured man.

Our neighbors are right on our doorstep; if we don’t even know their names, if we don’t know anything about them, how will we know how they might be hurting? How will we know what their needs are? How will we know how we can love them?

Jesus doesn’t answer the lawyer’s question of “Who is my neighbor?”—in other words, “Whom am I obligated to help?” (I don’t know if you’ve ever been the object of someone’s obligation, but it isn’t fun.) Instead, Jesus flips the script and asks, “Which of these three, do you think, was the neighbor to the wounded man?” The sentence can also be translated, “Which of these three proved himself by his actions to be a neighbor?” He’s saying, “Instead of asking whom you’re obligated to care for, why don’t you ask whether you’re being a good neighbor? Are you someone who helps others in need, regardless of language, religion, ethnicity; regardless of whether you like them or not, or whether they get on your nerves or not?” See:

love isn’t what you feel when you like someone;

love is what you do to care for someone.

Jesus is saying to the lawyer and to his audience, “You’re following the letter of the law but forgetting the spirit of the law. You’re obeying the minutiae of the law but you’re neglecting the Great Commandment. Remember what you said a few moments ago—love the Lord your God and love your neighbor as yourself?” Years later, the Apostle Paul would echo Jesus, in Galatians 5:14: “For the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself,’” and then in Romans 13:10: “Love does no wrong to a neighbor; therefore, love is the fulfilling of the law.”

But it’s real easy to do, isn’t it?

- To stick to the letter of the law and forget that God is calling us to the higher standard of love.

- To have something we can check off our list so that we can put it away and not worry about it again rather than continually committing ourselves to the constant work of love.

- To find an excuse for not going out of our way to help—I don’t have time, I’m too busy; it’s too costly.

Sometimes, for as much as we say we want to be like Jesus, we actually don’t. We don’t want the inconvenience and we don’t like the sacrifice it’s going to demand of us. Being like Jesus means I can’t always be about my agenda; when someone is rude to me, I can’t be rude back; when I see the person on the street, I can’t just walk past them without looking at them, saying a word, praying for them, helping if I can. The life Jesus calls us to—the life we were made for—is a challenging one because it won’t let us sit where we are. Jesus doesn’t just ask us to think about these things and come up with the right answer; what does he say? “You have answered correctly; do this and you shall live.”

“Dear children, let us not love with words or speech, but with actions and in truth” (1 John 3:18). What if we loved our next-door neighbors? Not just like:

- Okay, next time they get rowdy, I won’t call the police straight away;

- Next time they annoy me through the walls, I’ll try to be a little more patient and just let it go instead of thinking bad thoughts and talking crap about them to all my friends …

… but actually, by the power of the Spirit of God, beginning to care about what happens to them and being interested in what God might be doing in their lives.

And we do this—we care about loving our actual, flesh-and-blood, next-door neighbors better—because of what Jesus did for us. “We love because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19). See the story of the Good Samaritan is, in some ways, the story of Jesus. Even though it wasn’t socially acceptable, Jesus came and took care of us; when others passed us by, he put his life on the line for us; he paid for us to be brought back to life, even at cost to himself; and even though the law says we all have sinned and the wages of sin is death, Jesus refused to just stick to the letter of the law but, going beyond that, loved us so much that he gave his life on the cross so that we might live. We love God, we love our neighbors, because he first loved us.

The homework for this week is threefold:

- LEARN the name of one of your unknown neighbors this week and fill in their info on your block map. Take this home and stick it to your fridge or the back of your front door to remind you.

- PRAY for a neighbor—whose name you may already know or not—that God would provide you an opportunity to have a conversation with them.

- DO something to bless a neighbor.

I’m real excited about this series because I truly believe that God is going to do something great in and through those of us who choose to step out. But I’ll be honest: I’m also a little nervous, because we aren’t just going to be asking you to respond by thinking about something; we aren’t just going to be presenting you with a good argument or with the right answers or with what the Bible says so that you can go away and tell someone else about the cool things you heard on Sunday; we’re going to be asking you to do it—to do what Jesus says.

As I’ve said, I’m on this journey too: this is challenging to me too. There are times when I give freely and joyfully of my time and energy to serve and care for my neighbors but there are also times when I really don’t. I don’t always love my neighbor as myself, but I’m trying more and more, by the grace of God, to love out of the love of God. Because I think that’s what God is calling all of us to; I think that’s the better way of life that God wants for all of us; I think that’s how our city is going to be changed—by all of us learning how to love our neighbors better.

What if we all did what Jesus said and loved our neighbor?

The thing about the commandment, “Love your neighbor,” is that it’s real simple; and yet, when actually done, has the power to transform a street, a block, a neighborhood, and yes, even a city.

I believe that.