[Adapted from yesterday’s message at The District Church, “Savior, Messiah, and Lord.”]

I think Luke 2:10-12 captures the message of Christmas pretty perfectly:

Do not be afraid, for see—I am bringing you good news of great joy for all the people: to you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign for you: you will find a child wrapped in bands of cloth and lying in a manger.

Christmas is good news, right? Jesus being born is good news, right? That’s what the angel said to the shepherds, that’s what Christians believe. But as I was praying over this passage in preparation to preach yesterday, I had to ask myself again: “Why is the birth of this child, over 2,000 years ago, good news? What does that have to do with us today?”

In these verses, we see that Jesus fulfills three roles—savior, messiah, and lord—and over the years, these terms have all become staples of “Christianese,” easy for believers to throw around without actually thinking about what they mean and just jargon to people who don’t follow Jesus or who are new to this stuff. And I think it’s as we unpack these terms—unwrap them, so to speak—that we’ll find and understand the good news.

Savior. In Greek, the word is soter, which simply means “one who saves” or “one who rescues” from a desperate situation. “Savior” was also a term in the Hebrew Scriptures that was commonly, and almost exclusively, used for God. In Isaiah 43:11, God says, “I am Yahweh, and besides me there is no savior.” Most clearly for the people of Israel, God had been their savior—he had demonstrated his saving power—when he rescued them from slavery in Egypt through the leadership of Moses. And at the time of Jesus’ birth, the people were again being oppressed: this time, they were living under Roman occupation, and they were again crying out to God to rescue them, crying out for a savior.

Messiah. This word comes from the Hebrew mashiach, meaning “anointed” or “anointed one,” and this referred to the practice of anointing a person with oil, a symbol of God’s presence and blessing, usually to fulfill a certain mission or task on God’s behalf. For instance, even before David killed Goliath, when he was still just a shepherd boy, he was anointed by the prophet Samuel to be the next king of Israel. And by the time of Jesus, the term ‘messiah’ had come to hold in itself all of the expectations of the people of Israel for someone who would usher in the kingdom of God, someone who would inaugurate the reign of God: that time when everything would be set right, when injustice and oppression would be ended, when the wicked would be judged and the righteous vindicated. This is from Isaiah 61:

The spirit of the Lord GOD is upon me,

because the LORD has anointed me;

he has sent me to bring good news to the oppressed,

to bind up the brokenhearted,

to proclaim liberty to the captives,

and release to the prisoners;

to proclaim the year of the LORD’S favor,

and the day of vengeance of our God;

to comfort all who mourn …

The people of Israel were waiting for the one anointed to carry out God’s mission; they longed for the one who would come and set things right.

Lord. We don’t live in the Middle Ages any more, but this was a deferential title for someone in authority over you, someone of higher status than you, someone you would obey, someone who was your master. When you called someone, “Lord,” you were communicating that that person was worthy of your loyalty, your obedience, and your trust. So when we refer to God as “Lord,” what we are communicating—whether or not we back this up with our attitudes and actions—is that God is worthy of our loyalty, our obedience, and our trust. As the great missionary Hudson Taylor said:

Christ is either Lord of all, or he is not Lord at all.

But the thing is, God was not the only “Lord” around at the time of Jesus’ birth. The story begins, “In those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus …” Caesar Augustus was the first emperor of Rome, and there was a common saying among Romans at the time, a sort of pledge of allegiance, that said, “Caesar is Lord.” There’s also a fascinating Greek inscription from the year 9BC, during the reign of Caesar Augustus, found in the city of Priene, in modern-day Turkey:

Since providence … has ordered things in sending Augustus, whom she filled with virtue for the benefit of men, sending him as a savior both for us and for those after us [this word ‘savior’ is the same one that is used in Luke’s gospel to refer to Jesus], him who would end war and order all things [Prince of peace, anyone? The Messiah who would set all things right, perhaps?], and since Caesar by his appearance surpassed the hopes of all those who received the good tidings, not only those who were benefactors before him, but even the hope among those who will be left afterward, and the birthday of the god was for the world the beginning of the good tidings [gospel, good news!] through him … (emphasis added)

This inscription is referring not to Jesus, but to Caesar. See, his adoptive father, Julius Caesar, was deified after his death, which began the practice of recognizing all Roman rulers as gods. In fact, one of Caesar Augustus’s titles was Divi filius, which means ‘Son of God,’ or ‘son of the divine.’

Even two thousand years ago, people were desperate for help that would come from beyond themselves and they were looking for it. The inscription tells us how loyal citizens of the Roman Empire would see Caesar as a rescuer, a savior, a god, who would end war and set all things right. And you know what? A couple thousand years later, not much has changed—at our core, we’re desperate for a rescuer and a savior, for God to end war and set all things right, even if we don’t admit it.

Because we don’t often think of our need to be rescued, do we? That’s not a common cultural assumption. Once upon a time, maybe—fairy tales would tell of damsels in distress who needed to be rescued—but for the most part in Western society, we’ve left behind many of those patriarchal frameworks. Now, it’s a case of us all being self-sufficient, do-it-yourself kind of people: I don’t need to be saved from anything, and if I did, I’d do it myself! And yet, understanding the reality of our situation can be the key to determining whether we see Christmas as just another tradition or, as the angel described it, “good news of great joy.”

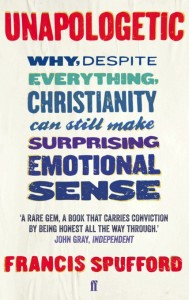

The reality is that you cannot save yourself, no matter how hard you try, no matter how much you want to. Because of sin: “For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23). Sin is something that gets in the way of our relationship with God and with each other; it’s destructive like that. English writer Francis Spufford describes sin as “the human tendency to [screw] things up.” He continues:

The reality is that you cannot save yourself, no matter how hard you try, no matter how much you want to. Because of sin: “For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23). Sin is something that gets in the way of our relationship with God and with each other; it’s destructive like that. English writer Francis Spufford describes sin as “the human tendency to [screw] things up.” He continues:

what we’re talking about here is not just our tendency to lurch and stumble and screw up by accident, our passive role as agents of entropy. It’s our active inclination to break stuff, “stuff” here including moods, promises, relationships we care about, and our own well-being and other people’s … (Unapologetic, 27; emphasis added)

Imagine the closest relationship you’ve ever had or could ever have, and now imagine tearing that in two. That’s what sin does, because the closest, most intimate, most wonderful relationship that you were created for was the one with God, your Creator, your heavenly Father, your Sustainer, the one who knows you inside and out, the one who loves you no matter what, the one who desires your good even more than you do. And sin inserts itself between you and God, between you and other people, and it causes a rift, a chasm.

And that’s what we do all the time and all over the place—screw things up—intentionally and unintentionally, with God and with other people:

- when we’re having an argument and we refuse to give up the fact that we’re right even though it’s destroying the relationship;

- when we choose our own comfort over the effort it takes to help someone in need;

- when we give in to our addictions for the hundredth time even though we just said we wouldn’t;

- when we hurt someone’s feelings completely by accident because we didn’t understand their history or their upbringing or we thought the way we see things must be the way everyone else sees things;

- when we don’t treat our family members with honor and love and respect because we’re busy playing with our phones or our new gadgets or zoning out in front of the TV.

That’s what sin looks like. That’s what we have no hope of getting ourselves out of, because it’s just so pervasive that we aren’t even always aware of it. That’s what we need saving from; and so we need a Savior.

We need a Messiah to set all things right and to usher in the reign of God in this world by bringing the Spirit of God into our lives so that we might be more of who God created us to be, lovers of God and of our neighbors, not just the end results of trying harder. We need a Messiah so that the world might be all that it was created to be.

We need a Lord, a master, to show us a better way of living, to lead us and guide us in a world that is full of voices and obligations and pressures and anxiety and fear. Everybody’s telling you the way to do things: advertisers, your colleagues, your boss, that random person whose blog you read, your siblings, your parents, your kids, your significant other.

But there is only one who knows the path of life and can show us the path of life; there is only one who can restore all things and redeem all things; there is only one who can save us from all our sins; and that is Jesus—Savior, Messiah, and Lord.

Of course, let’s not forget Luke 2:12, which would be so easy to pass over and yet is so quintessentially God and such a key part of the gospel story: “This will be a sign for you: you will find a child wrapped in bands of cloth and lying in a manger.” If you’re familiar with the Christmas story, you probably won’t bat an eyelid at that statement. But think about it for a moment: the angel has just announced that there’s great news, God is coming to save his people, a Savior is here, God’s chosen one.

If someone came up to you today and said, “Great news! So-and-so is going to bring about world peace,” you’d probably think of a political leader, someone who’s well-known and well-protected, someone with a lot of influence and clout, someone who’ll get things done. You wouldn’t think of a baby, would you? I mean, how is a baby going to save us?! He’s wrapped in swaddling clothes, which means that not only is he a baby, his arms and legs are tucked in tight! And he’s lying in a manger. Again, we’ve gotten so used to the term “manger” that we would be forgiven for thinking that that was just another name for Jesus’ bed. It was a feeding trough! For animals! Because there was no room for the family in the house!

What kind of rescue is this chosen one going to accomplish, who is in the form of a baby wrapped up in strips of cloth? What kind of leader is this who sleeps not in a palace or a high security compound, who doesn’t even have enough influence to get a spare room, has to sleep in a borrowed food container for oxen, and whose arrival is announced not on a public stage for all to see but to shepherds pulling the nightshift out in the fields?

Well, I’m glad you asked!

It will be the most complete rescue, it will be the most wonderful restoration; and he will be the greatest leader to ever walk the face of the earth, the one who will show us who God is and who we were created to be, the one whose power is the power of love and humility and sacrifice, the one who lifts up the lowly and brings good news to the poor and release to those in captivity and healing to the hurting and broken.

This is part of the surprise of Christmas. After all, the word “Christmas” is a conflation of “Christ’s Mass,” that is, the worship of the God who came as a human baby into the darkness of the night two thousand years ago, who comes also into our darkness and our fears and our longing, to bring light and hope and fulfillment. A Savior has been born to us, God’s anointed, who will be the Lord, the herald and harbinger of the kingdom of God, and the one who will set all things right. And he shall come not with a trumpet-in-your-face, unavoidable demonstration of power that will blast you into submission, but as a baby, swaddled, and lying in an animal’s feeding trough. Because that’s how love works. That’s how God works. Frederick Buechner wrote this in The Hungering Dark:

Those who believe in God can never in a way be sure of him again. Once they have seen him in a stable, they can never be sure where he will appear or to what lengths he will go or to what ludicrous depths of self-humiliation he will descend in his wild pursuit of man. … And this means that we are never safe, that there is no place where we can hide from God, no place where we are safe from his power to break in two and recreate the human heart because it is just where he seems most helpless that he is most strong, and just where we least expect him that he comes most fully. (13-14)

That’s why Christmas is good news. And I hope it’s good news for you this week.

Merry Christmas!