[Part 2 of a four-part adaptation of my message, “Our Daily Bread.”]

To begin with, some of you might point out that in Matthew 6:8, Jesus says, “Your Father knows what you need before you ask him,” which echoes Psalm 139:4—“Even before a word is on my tongue, O Lord, you know it completely”—so why even bother voicing these requests? God knows, right?

Well, yes, he does, but there’s a great quote from P.T. Forsyth, a Scottish theologian who lived about a hundred and fifty years ago, that I found helpful in how I understand this. He said, “Love loves to be told what it knows already … It wants to be asked for what it longs to give.”

I have a four year-old niece called Amy, who lives in Southern California, and when I’m back there, I always make sure to spend some quality time with my brother’s family. Now before every meal, of course, the kids have to go wash their hands, and Amy’s not tall enough to reach the bathroom sink on her own, so there’s a stool in there to help. And she’s old enough and smart enough to grab the stool and wash her hands without help, but this one time she turned to me and said, “Will you help me, Uncle Jus?”

I have a four year-old niece called Amy, who lives in Southern California, and when I’m back there, I always make sure to spend some quality time with my brother’s family. Now before every meal, of course, the kids have to go wash their hands, and Amy’s not tall enough to reach the bathroom sink on her own, so there’s a stool in there to help. And she’s old enough and smart enough to grab the stool and wash her hands without help, but this one time she turned to me and said, “Will you help me, Uncle Jus?”

Love wants to be asked for what it longs to give.

Pastor and author John Ortberg highlighted something in a recent sermon and it was a revelation to me, so I want to share it with you. Jesus lived in a time in which agriculture—farming—played a huge role in life; most farmers operated on the yearly food cycle of sowing and harvesting. Back in Old Testament times, when God was establishing the people of Israel as his own, he gave instructions for creating a culture of generosity; so for instance, in Leviticus 19, he says to the farmers, “Do not reap to the edges of the field; leave the gleanings—the leftovers—for the poor and the immigrant,” those who have no way to fend for themselves. Moreover, farmers were instructed to provide for the local poor—the poor in their towns—about a week’s worth of food, so they wouldn’t have to come back and ask every day. But for the itinerant beggars, the poorest of the poor, those who traveled from town to town, they would provide only enough food for the day.

So when it came to food, farmers operated on the yearly cycle, the local poor operated on a weekly cycle, and the poorest of the poor operated on a daily cycle. In Jesus’ day, the normal prayer for food that rabbis taught was, “Bless upon us, Lord our God, this year and all its types of produce for good.” It was common practice for disciples to ask their rabbis for their own versions of these prayers—like customizing them for their team; so, in Luke’s account of this incident, the disciples come to Jesus and say, “Rabbi, teach us how to pray.”

And Jesus says, “Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name, your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread.”

This is the prayer of the poorest of the poor—“Give us what we need for this day; that’s all we’re asking.”

There’s an interesting episode in Mark 2. One sabbath, Jesus and his disciples are walking through some grainfields and the disciples begin to take some of the heads of grain. These aren’t their fields—they don’t own any fields—so they’re taking food that doesn’t belong to them! And they get in trouble with the religious leaders. But they get in trouble with the religious leaders not for taking the food, but for doing what’s considered work on the sabbath. Why is this? Because that food was left for them—remember: “Do not reap to the edges of your fields; leave the leftovers for the poor …”

So when Paul writes in 2 Corinthians 8:9, “Christ, though he was rich, for your sakes became poor,” he actually means poor—not just poor compared to the riches he left in heaven; like, actually poor.

I want to suggest that this means two things for how we pray this line. First, when Jesus taught his disciples—when he taught us—to pray, “Give us this day our daily bread,” he was identifying with, and asking us to identify with, the poorest of the poor. The life of faith is not one you can walk on your own, with no reference to those around you, and especially without regard for those who are less fortunate. God made every single one of us—rich and poor—in his image; Christ lived and died and rose again to rescue and redeem every single one of us—rich and poor. We are called to be our brother’s keeper and our sister’s keeper, to care for the poor, or as Matthew describes them later in his gospel, “the least of these.”

In prayer, even when we make requests, even when we ask for things, God doesn’t want us to withdraw into our own self-centered shells, as it’s so easy to do. That’s not what prayer is about, not even petitionary prayer. So maybe when you give thanks for your food … first, you don’t take it for granted–after all, it’s real easy to just go through the motions, and second, you pray for someone who doesn’t have food, that God would provide their daily bread, too. Or maybe when we ask God for something, we ask God to open our eyes to someone else who might have this same request, and we pray for them too.

The second thing I think Jesus means when he tells us to pray for our daily bread is that you can ask for what you need.

For some of us, “Give us this day our daily bread” is a strange request—here’s the material world intruding on the realm of the spiritual; prayer’s about asking for patience and wisdom and grace and forgiveness and joy and all these other intangible things, right? And the older and wiser and more mature we get, surely the less self-focused we should be, the less our own requests should factor into our prayers, and the more we should be able to just bring the causes of others—especially those less well-off—before God. That’s what I thought growing up, and maybe you may not say that, but when you stop to think about what you pray for, maybe that’s you.

You might think that you really shouldn’t bother God with the small, seemingly petty, definitely mundane things in your life. We can ask him to help us forgive someone who’s hurt us deeply; we can ask him to heal someone who’s dying of terminal cancer; we can ask him for guidance and wisdom and clarity about whether or not we should get married to the person we’re dating; but he’s not really interested in the little things, is he? He doesn’t care about a meeting we might have this morning, or a leak in the roof, or a broken heel. We can handle that stuff!

You see, we can think that prayer is to God as decisions are to the President. Barack Obama has a lot of decisions to make, and only a limited amount of time to make them—he is only human. So if there are easy decisions to make, they’ll get made further down the chain of command; responsibility is delegated, so if something does make it to the President’s desk, it’s because it needs his attention.

And in the same way, we can think that we should only bother God with the really important stuff, only with the things we can’t handle. And there’s a real power that comes from asking God for the seemingly impossible; there’s a kind of faith that comes out of that; and we should definitely, definitely ask God for the ‘bigger’ stuff. But here’s the thing: God is eternal, God is not bound by time and space and the finiteness of humanity, God does not have a limited capacity that he has to carefully divide up between the billions of us who are clamoring out our requests.

More importantly, God is, as we looked at a moment ago, our Father.

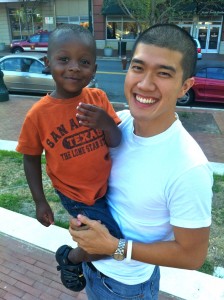

Now I don’t have kids of my own, but sometimes I get to go pick up Elijah, Amy and Aaron’s three year-old son, from school. I’ve known Elijah since he was only a few months old, and I care about him as much as I care about my own nieces and nephews. And so when I pick him up from school and as we walk home, I ask him about his day: I want to know what he did that day, I want to know what he learned, I want to know if he had fun or if he cried. It gives me joy to hear him talk, to hear him share, to hear about his life. Because I love this little man, I take an interest in his life. There is nothing too mundane; and there is nothing too small.

Now I don’t have kids of my own, but sometimes I get to go pick up Elijah, Amy and Aaron’s three year-old son, from school. I’ve known Elijah since he was only a few months old, and I care about him as much as I care about my own nieces and nephews. And so when I pick him up from school and as we walk home, I ask him about his day: I want to know what he did that day, I want to know what he learned, I want to know if he had fun or if he cried. It gives me joy to hear him talk, to hear him share, to hear about his life. Because I love this little man, I take an interest in his life. There is nothing too mundane; and there is nothing too small.

And in the same way, Jesus tells us, God cares for us, as our heavenly Father, infinitely more than human fathers and mothers ever could. He says in Matthew 7:

Is there anyone among you who, if your child asks for bread, will give a stone? Or if the child asks for a fish, will give a snake? If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give good things to those who ask him!

God’s not out to get you. No, God cares for us so much more than we care for those we love. There is nothing too mundane; and there is nothing too small.

Asking for the food we need to make it through the day is about the most basic thing you can ask for, and if Jesus doesn’t look down on it, I don’t think we should either. So don’t let anyone tell you that bringing your humblest, most ordinary, most practical requests to God is somehow less spiritual. Nothing is more important to God our Father than what we are going through, whatever that might be. These things—great and small—are important to him because they are important to us. Just as I love hearing Elijah share the smallest details of his day at school, so God longs to hear from us the smallest matters of our lives. It delights him when we share; it gives him joy when we ask him for things that he desires to give us—remember, “Love loves to be told what it knows already … It wants to be asked for what it longs to give.”

As human beings, we have physical, material needs—food, shelter, clothing—and for most of us these things aren’t an issue, but for many in our city, they are. In 2007, there were 200,000 children in the Greater DC region at risk of hunger, including 1 in 2 children living in the District itself.

How can we be asking for our daily bread, where “our” means not just me and the person I’m praying with at this particular moment, but the people of this city that we live in?

Stepping out from the literal understanding of our daily bread, what else do we need for our day? Maybe some of those intangibles we mentioned earlier: peace when you’re facing a tough classroom or work situation, joy when you’re just feeling like your back’s against the wall, hope when you can’t see even the faintest glimmer of light in your situation, faith to trust that God your Father hears you when you ask. You can pray for these things too; you can ask your Father for these things.

“Give us this day our daily bread” is both very basic and very desperate. Remember, this is the prayer of the poorest of the poor. It’s very basic, to do with the stuff of life: “Give us food for today.” And it’s very desperate: “Give us food for today.”

And that leads us into tomorrow’s piece: How to ask.

Pingback:Prayer, the Kingdom of God, and Desperation | JUSTIN FUNG